The Artist’s Dilemma

That dead coyote lay on the edge of the road.

I’d pass it driving the girls to school, wondering why no DPW crew had removed it.

Drivers whizzed by the luminous thing as if it were a figment of my imagination.

It was spring and things were waking up.

Finally I could no longer resist the coyote’s call. Intact road kill is a rare chance to study something wild and uncatchable up close. So one cool morning I gave up thinking of what other drivers thought of me stopping at a dead animal, and pulled over.

She was a she. Young, prime, full-furred, perfect. Her pose was that of a coyote running. I looked at her for a long time, running my palm over the tips of her lush coat, her elegant face and dancer’s paws. No blood, no bloat. What killed her? Truck, or poison?

The specter of artist Helen Miranda Wilson’s voice rose like Marley admonishing drivers who passed car-struck animals without stopping to take them off the road. Impractical be damned, it was, she said, a matter of dignity.

I took the beautiful creature by her paws and pulled her into the narrow copse of trees between a private road and Rt. 137.

So light for her size! I covered her body with branches large enough to camouflage her from humans and vultures but open enough for the elements to do their work. Then, like a lily on a grave, I laid a nearby wild turkey feather over her crypt of sticks.

Each day I drove past the trees knowing she was there.

In November I went to find her again. To my disappointment she seemed to have vanished – hauled away by ants? Until my eyes began to slowly differentiate a delicate tobacco brown jawbone from the soil around it.

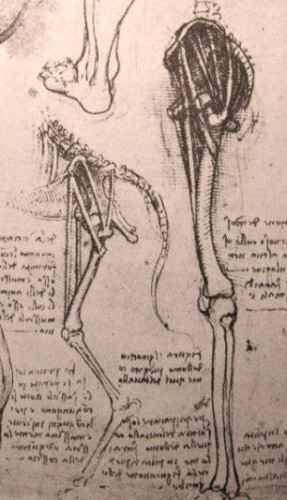

Carefully I lifted away the branches and found what I’d been looking for, a nearly intact coyote skeleton. This arrangement of thin bones, embedded like fossils in the ground, was so disconcertingly small and spare compared to the robust body I’d covered in spring. Gone was any trace of fur or muscle, sinew or organs – all had melted back into the digesting earth.

Like some blissed-out archeologist I brushed the brown soil from each brown bone and placed them in an old plastic box, grouping rib bones from leg bones, neck bones from tail bones, teeth from claws, with the hope of reassembling her puzzle as best I could later on.

The most complex cluster of bones was the paw, with its mosaic of individual metatarsals, knuckle bones and translucent claw sheaths – a miracle of engineering cupped in the palm of my hand.

In my excavation I discovered the source of her death: one child-sized pelvic bone wrenched from its twin and broken in half, a shattered vertebrae, a broken femur.

I have my reasons for collecting bones.

1- Other than chicken bones how often in life do we get the chance to hold, examine and contemplate these divine Erector Sets first hand?

2- Bones cultivate healthy humility in an artist forced to confront the “Why Even Bother?” component of art-making when faced with the aesthetic sophistication of the simplest fibula. Buried within the artist’s very body is a modular sculpture of exquisite and logical elegance that surpasses her highest capacity as a creator of things.

Unstoppable curves slide into bladed edges, bloom into bald knobs, narrow into valleys. Some bones are as Zen as a reed, a riverbed. Others, like vertebrae, go all baroque and cartoonish, winged and pierced yet precisely symmetrical. There’s no turn of line, no fitted curve however lyrical, without necessary purpose. Bereft of the superfluous, the indulgent, the decorative or the trendy, each bone is an act of individual aesthetic truth, standing alone and married to the whole.

Try THAT one artist, O mimic of God!

I laid out the coyote’s skeleton on a worktable. It was a very intimate thing to do, handling her innermost core without her permission. She looked strange out of context.

I had held her head and now held her skull as if I had pressed my hand without resistance down to what lay beneath.

It is my intent to draw every one of her bones one by one.

If attention is a form of reverence then every drawing will be done in thrall of what I can’t do.